I put some thoughts together on the European early-stage VC funding gap from a founder’s perspective, after recently re-reading Melinda Elmborg’s1 piece in Forbes, and Atomico’s State of European Tech report.

The funding gap is well-defined in the article, but the highlight for me was that from 2016 to 2019, the number of pre-seed deals in Europe fell from 5,300 to 3,500. Contrast this with the number of deals above $2m in size growing by roughly 50% in the same timeframe, and you can begin to see the divergence.

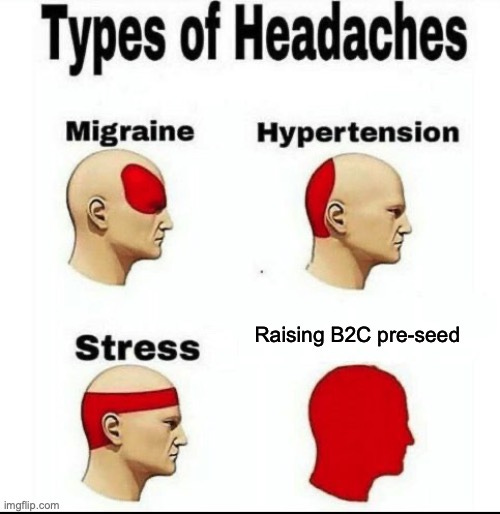

We’ve seen an explosion in SaaS, impact, and deeptech investments, each approximately trebling in allocation, but the consumer space seems to be falling out of favour.

There are many factors at play here – the main ones, as I see it, are:

Overall risk appetite

FOMO and social proof

‘Free call-option’ nature of angel & VC investing

Over-indexing on timing

Opaque investment criteria

Risk Appetite:

Most conversations I have with European investors tend to focus on the downsides of “What if…”, rather than on the upside potential. In reality, a few core things need to go right, and the rest can be fixed with momentum and eventual scale.

If all of our unit economics were concrete, and I had reams of user data and a tech-stack creaking under the weight of customer demand, we wouldn’t be having this conversation – or, it would be a Series A round, with an extra zero added to the valuation.

A fundamental part of Silicon Valley’s success is the rampant optimism that is core to the culture. Unflappable bullishness and a healthy regard for failure are traits we’d do well to at least partially embrace.

“We’d like to see more traction” — well yes, so would we, that’s why we’re asking for funding to make that happen faster! A 20-100% organic uptick in demand shouldn’t have much bearing on your investment decision. We’re raising the round to get a 200x multiple of current demand, and the ability to achieve the former isn’t much linked to the latter.

The queries you have around unit economics won’t be solved in a few months. That data is often a barely-reliable picture by Series A. In fact, many companies post-IPO are still burning cash, so why are we expecting these answers at pre-seed?

Raising pre-launch is arguably easier than doing so with bare-bones initial traction, as “selling the dream” is easier than pitching with some crumbs of data from a public launch.

“If you can see the trunk poking out from under the rug, you can infer the rest of the elephant.”

If traction really is your barrier to investing, at least specify which milestones would allay those concerns. All too often I hear “we’d like to be involved in your next round!” – there won’t be a next round if this one doesn’t materialise, and there are specialist investors with far deeper pockets and networks at that stage that you’ll be competing with. Why would working with you be appealing to a founder in that scenario, if you didn’t back them from the beginning?

The way I see funding rounds’ purposes:

FF&F: Build MVP, prove initial supply/demand, market research, set hypotheses

Pre-Seed: Build v1.0, test go-to-market strategies, early scalability proof for users/customers, hire core team

Seed: Jet-fuel for scaling to a few core markets, using lessons learned on unit economics and effectiveness of GTM strategies. Build on initial team and product.

Series A+: Hire excellent execs/managers, build out teams, expand geographically, broaden product offering, refine processes (repeat)

Bottom-line: European funds are asking too much of companies at an early stage; expecting metrics that would normally be found in the subsequent stage of the above lifecycle.

Broadly, at pre-seed, you need:

Capable, scalable founders

A good working dynamic

Complementary skillset

Market knowledge/experience (preferable)

Buckets of grit

An MVP and a vision for the product

The funny part is that the idea itself doesn’t need to be particularly spectacular – the above combination is empirically more than enough to cram a square peg into a round hole long enough for everyone to exit and buy a big boat.

Or at least long enough to pivot into something which takes off, as is so often the case in B2C.

FOMO — “Who else is investing?”

A lot of early-stage investment rounds, especially in the consumer space, seem to be hype-driven FOMO-fests. It’s an odd phenomenon, but essentially it’s the pareto principle in action: 80% of the capital flows to 20% of the deals.

Not all of that capital can squeeze into every round, so what happens? Inflated valuations and survivorship-bias anecdotes of “oh it was easy to raise! We had VCs battering our door down and offering us a new Porsche as a deal toy!” — these are the exceptions, not the rule. Crucially, they’re also not necessarily the best opportunities; just that they managed to get to demand escape-velocity.

I’ve also found valuation to be a topic of concern among angels and newly-minted VCs. Within reason, arguing over valuation at this stage is misguided – in fact, it jeopardises investor outcomes. Returns from the venture model come from the few ‘fund-returners’, and then ensuring you double-down on those companies in as many subsequent rounds as possible to minimise dilution.

For the 100x-ers or fund-returners, you don’t care whether pre-seed was €2m or €5m pre-money, and for the 0-1x-ers, you especially don’t care. As long as you’re getting sufficient allocation and ownership, just get on the horse!

Free Call Option

If I had €10 for every ghosted email or Typeform submission, I’d have no further need to raise a round.

The problem here is that it’s almost in an investor’s best interest to ghost founders. If they don’t say “no” definitively, then they keep an open window to try to FOMO into a round if a respected investor later decides to back the company. It’s a big-stakes game of hokey-cokey.

“There’s too much competition in this space” cries the investor, who will go on to back the nth scooter company, Linktree competitor, and 4-minute grocery delivery business.

There’s a bizarre habit of being vague, or straight-up insincere, when giving the reasoning for a pass. Maybe that’s because it’s assumed that this insulates the founder’s feelings, or because it’s difficult to openly critique someone’s idea or strategy, but the end result is a breakdown of trust at best, or at worst, an impression that your decision-making and analysis is poor.

It also takes some (small) amount of time to respond to founders. I understand, of course, that funds are swamped with inbound, and time is scarce, but the effort : reward here is too favourably skewed to excuse.

In communicating openly, and in a timely manner, you’re showing respect for founders, and adding value. Insights into the genuine reasoning for passing can be instrumental data points for founders. It might inspire a pivot, or adjustment to the business which actually makes it a viable investment for your fund.

Even altruistically – in most cases, these founders have poured everything they have and more into their startup. Building is damn hard, fundraising is arguably harder, and so any sort of allyship or compassion goes a long way in boosting morale.

Unless you’re a solo LP/GP, it’s not your cash you’re investing – you’re a steward for it. Maybe the real carried interest is the community and network you build along the way.

Timing

There’s so much emphasis on ‘timing’ in early-stage investing, and perhaps with good reason. It can add tailwinds to an otherwise lacking deal, or add a real catalyst to a solid deal.

But the conventional wisdom in public investments is that you shouldn’t try to time the market. Why would that differ in private markets? There are products and businesses that are reliant on the zeitgeist, but I’m skeptical as to whether it’s a blanket pre-requisite.

I’d argue that in many cases, the “why now?” slide could be “why not now?”. The inspired, genius timing of successes seems obvious in hindsight, but can be invisible ex-ante. Equally, sure-bet, precision-timed launches fall flat, too, or become over-hyped which leads to further complications (Clubhouse, Peloton, Houseparty, etc.)

Waiting for a divine signal or green-light from the market might mean you miss the boat altogether.

Obscure / Opaque Criteria

“We’ll invest in consumer pre-seed on the third Friday of September, if it’s a leap-year and the founder’s a Taurus.”

“We invest in early stage tech” – what does that mean? If you’re a JPM M&A analyst, you might think that means Series B or C. If you’re a founder, that could mean you’re an angel syndicate, or have a minimum ticket size of €25k, when you’re actually a Softbank-esque behemoth.

Funds will spend a small fortune on a crazy homepage with a radically difficult UX, but won’t list what they do— seemingly for fear of appearing uncool, or missing out on an ad-hoc deal outside of their usual scope.

This adds to the noise in their inbound dealflow, and wastes time on both sides.

Summary

Before we fix early stage investing, we should get the basics right: answering emails, and being transparent. VCs should know better than most that short-term games don’t pay long-term prizes.

As a VC you might loathe my current startup with every fibre of your being, but what if my next idea is a hot one? What if my best pal starts something with a cap table more exclusive than Berghain’s guestlist? How many ex-founders end up working in VC? Burning bridges by ghosting makes no sense — you might think you’re saving us the pain of a negative outcome, but in fact you’re adding insult to injury.

A quick, honestly-reasoned ‘no’ is 100x better than an indefinite ‘maybe’. Even “we’d be interested if you hit X, Y, Z milestones”. Blunt, hard-hitting feedback has been core to some of the best VC interactions I’ve had (often from US funds) – and has played no small part in forming the business we’re running today. If a Partner at FJ Labs (649 portfolio companies) can respond on the same day with detailed, thought-through feedback and specific KPIs at which they’d invest, your fund can do the same within two weeks.

This doesn’t need to be a time-suck either – it can be pretty much automated, if not conducted by one of the army of willing, capable students looking to break into VC through an internship. Use of a solid CRM system with auto-email generation, and a few lines of feedback are a step in the right direction. An example of a fund doing this well would be Point Nine in Berlin.

Conversely, I’ve had several pass emails which were blatant copy-pastes with no tailored feedback, but differing text size and font in the body than in the intro. That’s possibly worse than ghosting!

Instead of hitching rides on rockets that have already left the ground, we need to see more leaps of faith. This is how categories are born, redefined, and disrupted. A “venture” is defined as “a risky or daring journey or undertaking”. A VC fund unwilling to take risk is just a growth fund with smaller tickets and an office Peloton.

As discussed in the original Funding Gap article, foreign investors capitalise heavily on later-stage European tech success stories. It won’t be much longer before US investors, Solo-GPs, a Euro-AngelList, or the crypto-funding space pose a real competitive threat at the early stages in Europe — so it would be prudent to get a little more comfortable being trigger-happy with term sheets, and accepting of risk, or I imagine we’ll see the seed space eaten up by foreign investors, too.

Remember: it’s only a “pass” if the fund’s from the Passé region of France. Otherwise, it’s just sparkling ambivalence.